Editor's Choice

The (Sex) Bomb that Won the War

Harriet Brunsdon Jones

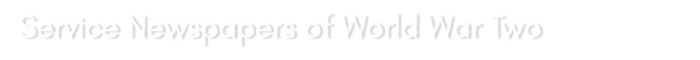

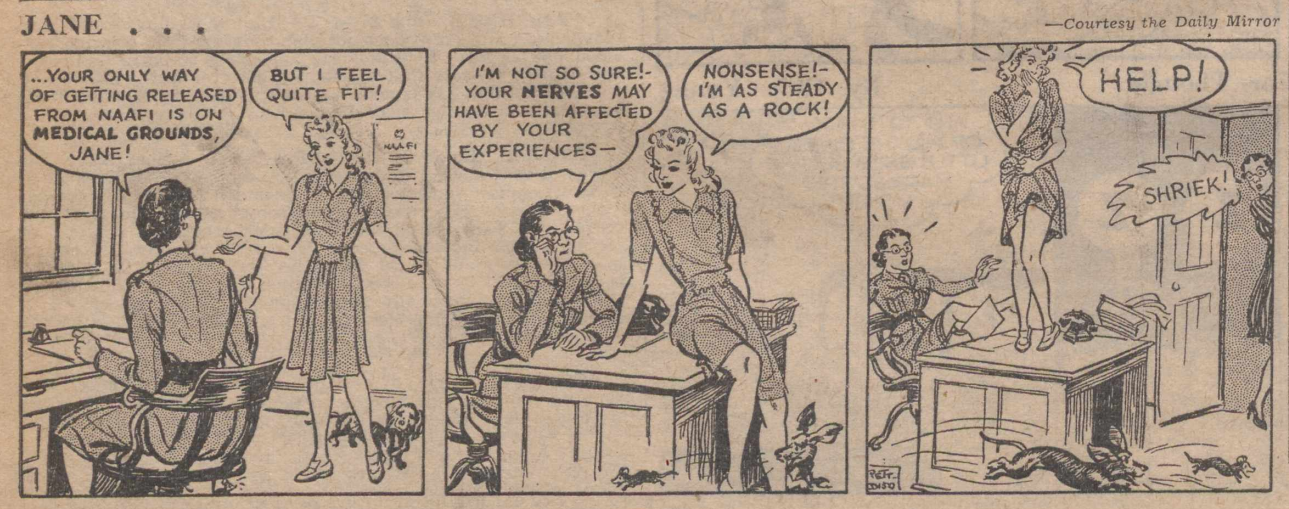

You can’t have a discussion about wartime journalism without mentioning ‘Jane’ – the racy British cartoon strip that kept morale high during the years of conflict. She scandalised, motivated and entertained in equal measure, garnering a cult following which lasted long after the peace was signed.

Jane started life in 1932 as a regular strip in The Daily Mirror, drawn by artist Norman Pett. Pett’s wife posed for his sketches in the early years, before other commitments took priority. Then in 1940 Pett teamed up with professional model Chrystabel Leighton-Porter, who became Jane as she was known and loved during the war years.

The running joke and popular appeal of Jane was her habit of getting into all manner of scrapes and invariably ending up losing some if not all of her clothes. The nudity element was outrageously cheeky for the time, but never smutty. Jane was always portrayed as being sweetly unaware of her sexual side, and her storylines, complete with patriotic plots and featuring her boyfriend Georgie Porgie and faithful dachshund Fritz, were respectful and light-hearted. It was this innocence that justified Jane’s near-constant state of undress to the moral standards of the day.

It’s not surprising, then, that Jane was such a hit with the troops. Starved of female company, and desperate for anything to alleviate the crushing boredom of a life steeped in routine and regulations, units all over the world hotly anticipated the arrival of newspapers containing the next Jane instalment. Although Jane was a Daily Mail cartoon, she was ‘borrowed’ by several service newspapers in order to distribute her to wherever the troops happened to be. Union Jack, Eighth Army News, Pacific Post, Good Morning, and The Maple Leaf all featured Jane at one time or another. Not only was she considered a reward for hard-working soldiers, she also came to embody the idea of what the men were fighting for. Stories of how she galvanised troops into action give her a legendary status even to this day. For instance, it was said that when Jane first appeared fully nude in the strip, the 36th Division in Burma stormed forward six miles in one day. Submariners heading off on duty would be out of touch with the rest of the world for weeks or months at a time, with no way of getting newspapers. To overcome this, some publishers allowed captains to take advance copies on board, under strict instructions to keep them under wraps until the official publication date. One story goes that when a certain submarine was sinking and the crew were expecting to die, they asked the captain to release all the copies of Jane that he had in his safe so that they could spend their final moments looking at her. Fortunately they lived to tell the tale.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill famously called Jane ‘Britain’s secret weapon’. Undoubtedly her contribution to the war effort is second to none, and her place in history is forever assured thanks to the continued exposure of her undergarments.

Good Morning: The Daily Service Newspaper That Wasn't

Jade Bailey

“Of all the branches of men in the forces,” said Winston Churchill, “there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.” It is not difficult to see why: the life of a submariner during the Second World War was a uniquely challenging experience. Submarines commonly spent weeks at a time away on patrol, during which time their crew were left without access to the newspapers and radios available to most other servicemen. Not only did this make keeping up with military and political developments in the war particularly difficult, it was harder for letters from their families to reach them, no doubt increasing the sense of isolation many of them must have felt. Trapped aboard poorly-ventilated ships, living in close quarters with their crewmates and facing the constant threat of a torpedo or a mine (over one third of the Royal Navy’s submarines were lost during the war), morale among the submarine force was understandably low.

“Of all the branches of men in the forces,” said Winston Churchill, “there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the submariners.” It is not difficult to see why: the life of a submariner during the Second World War was a uniquely challenging experience. Submarines commonly spent weeks at a time away on patrol, during which time their crew were left without access to the newspapers and radios available to most other servicemen. Not only did this make keeping up with military and political developments in the war particularly difficult, it was harder for letters from their families to reach them, no doubt increasing the sense of isolation many of them must have felt. Trapped aboard poorly-ventilated ships, living in close quarters with their crewmates and facing the constant threat of a torpedo or a mine (over one third of the Royal Navy’s submarines were lost during the war), morale among the submarine force was understandably low.

In 1942, the solution to this problem emerged in the form of Good Morning, a dedicated paper produced for the submarine force by an editorial team based at the Daily Mirror. Instead of being printed every day, the undated newspapers were produced in bulk print runs of numbered issues, with a stack being issued to every submarine before it left on patrol. The next number in the sequence was handed out each day, giving the impression of an ordinary daily newspaper. A total of 924 issues were printed - enough for over two-and-a-half years’ worth of daily copies - and the complete run, held by Imperial War Museums, is included in this resource.

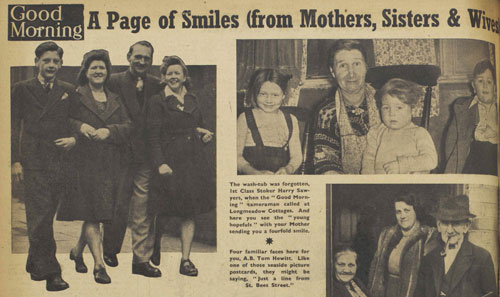

Printed weeks in advance, Good Morning necessarily lacks the up-to-date coverage of the war seen in more conventional dailies such as Union Jack or The Stars and Stripes. In fact, it often avoids discussing military matters or politics altogether, with content focusing instead on a more magazine-style array of stories, puzzles, cartoons and photographs. Pin-ups feature prominently, alongside scenic images of the British countryside, family photos sent in by relatives of submariners, and perhaps the most impressive collection of amusing photographs of cats seen before the invention of the Internet. News reports were replaced with historical anecdotes and various short fiction (printed under intriguing titles including “The Granite Woman and her Paramour” and “Secret of Cossack Horse That Went Flapping”). Good Morning was bright and cheerful fare, designed both to entertain and distract submariners while also providing an invaluable connection to home.

Good Morning’s positive contribution to crew morale was widely attested by its readership. “The coxswain brings ‘Good Morning’ round each morning at sea, and it goes down as good as a tot of rum at 11 o’clock,” one submariner wrote to the paper from the Mediterranean. Other reports speak of sailors gambling their rum rations over the results to the quizzes and puzzles, and of officers releasing their entire stock of unread issues to cheer the spirits of their men during desperate moments. Among numerous testimonials to the paper in its final number is a letter from Rear-Admiral George Elvey Creasy: “It falls on me to say, on behalf of all officers and men whose lives have been brightened by ‘Good Morning’ in innumerable hours of tedium, hardship and danger, ‘Our most grateful thanks. We shall not forget.’” ![Two children with a sign reading 'Sumbarines [sic] For Sale'. Good Morning, no. S132](/ContributeData/ServiceNewspapers/Views/Introduction/LBY_E_J_005199_5_121_0001.jpg)

The Stars and Stripes War Orphan Fund

Yulia Kovnat

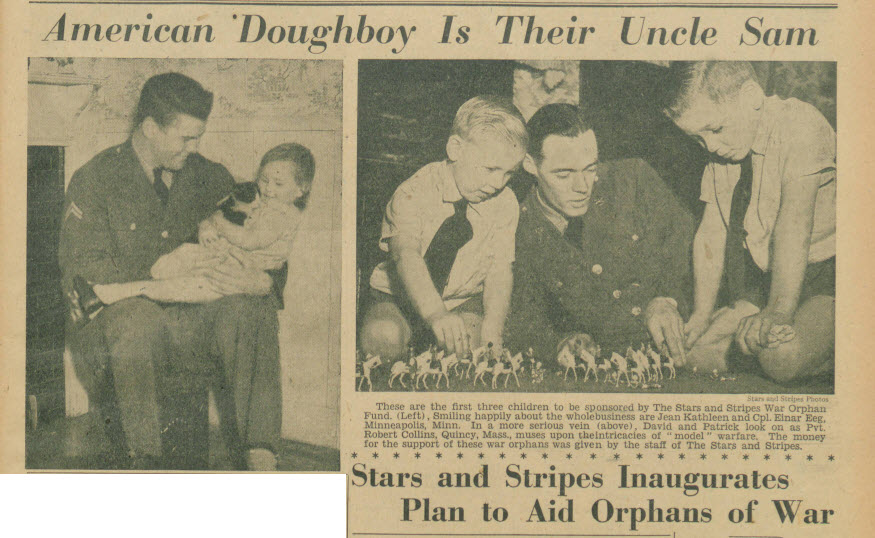

There are many stories of sacrifice, determination, and goodwill within the pages of this collection. Nevertheless, a particular note must be taken of the work carried out by The Stars and Stripes newspaper and its War Orphan Fund. Originating in the First World War, during the years 1918 to 1919, the program saw American soldiers ‘adopt’ nearly 3,500 French children at a cost of five hundred francs per child.(1) On 26th September 1942, the Second World War edition of The Stars and Stripes relaunched the campaign with the goal to raise a fund large enough to support 500 orphans for a period of 5 years. In conjunction with the American Red Cross, their goal was to “provide each child with £20 per year”; the equivalent of approximately £928 in 2017. The money was raised to enable “the purchase of some necessities and extras that orphan children are so often unable to enjoy”.

Under this program, the children selected for support or assistance included cases of unusual hardship. Whether that was due to the mother of the half-orphan being unable to work or the grandparents or guardians of a full orphan not being entitled to the same pension as a widow. The fund wanted to provide the orphans with ‘the extra things of life’ that they would have received ‘had they not lost their parents’.

Part of the appeal of the scheme was that those who contributed the full £100 – the sum needed for each child for the full five-year program – could specify the sex, colour of hair and age of the child they desired to assist. A photograph and a history of each child was sent to its sponsoring unit, which was advised of the child’s whereabouts and progress. The expenses of administration were borne by the American Red Cross and the organization visited the schools and homes of the sponsored orphans and supervised the expenditure of the money held in trust for their use.

The revival of the fund gathered instant support from the military, with Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, as the U.S. commander in the European Theater of Operations, called it “most appropriate”. He went on to say that he was “delighted to hear that The Stars and Stripes [are] presenting to the American Forces an opportunity of aiding orphan children of our Allies,” and that the newspaper “may be assured that the officers and men of my command are heartily in accord with this undertaking.” Thanks to the work of the newspaper, within eighteen months, The Stars and Stripes War Orphan Fund had raised more than £45,000 ($180,000). (2) It was so successful that the initial target of £50,000 was eventually raised to £100,000.

(1) Yank, 21 Feb 1943, p. 23.

(2) The Stars and Stripes, 14 Feb 1944, p. 3.

The Camp

Jacob Downey

Unlike the majority of newspapers in this resource which can easily be classed as either Allied or Axis, The Camp is unusual in that it could quite easily be classed as both. The paper was produced by a German staff for distribution throughout various prisoner of war camps to be read by Allied PoWs. How successful The Camp was in this objective is difficult to gauge, but the large number of PoW created newspapers would suggest that many found something lacking in The Camp’s editorial content.

The Camp certainly had some interesting features, including a section entitled The German Point of View a delightfully awkward attempt to both show the superiority of German thinking as well as trying to show that the Anglo-Saxon bond was not as broken as one might expect, despite the two nations being on opposite sides in the largest war the world had ever seen. There were cartoons lifted from Punch, albeit clearly by someone who didn’t fully understand the intricacies of British Service humour, articles supposedly written by PoWs that put a slightly unbelievably positive spin on imprisonment and perhaps most bafflingly German lessons that took up half a page and consisted simply of a wall of German text with no accompanying English explanation. Incredibly detailed articles on Cathedrals on the Rhine and the merits of different horse-riding methods might have provided a thorough examination of said topics, but it is somewhat difficult to imagine very many imprisoned servicemen devoting their time to reading up on German Gothic architecture. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that similar features tend not to be found in papers published by PoWs themselves.

The Camp also featured news articles, although to class them as such requires a somewhat loose definition of news. War news was provided, naturally extolling the brilliance of the German military, although as the tide of war turned in 1943 the articles in this section became increasingly selective in their content, including a very selective article on the surrender of German forces in Tunis in 1943. News from Britain was also provided, although in an attempt to never say anything too positive about the situation in Britain this section tended to feature a bizarre mix of mildly negative and seemingly inconsequential stories, epitomised by a brief article detailing the substitution of lunchtime oranges in schools with vegetables.

Whilst it would seem likely The Camp never have achieved much success as a newspaper it has nonetheless a real value. To us looking back from the present day it shows a fascinating insight into German propaganda, German perceptions of Britishness and an insight into the often-neglected world of PoWs. To the readership it was originally intended for, I think we can assume it probably got more use as a firestarter, material for paper aeroplanes and countless other applications, few of which I imagine involved reading it.

For a selection of PoW published papers see The Willenberg Echo, Wireville Gazette and The Clarion

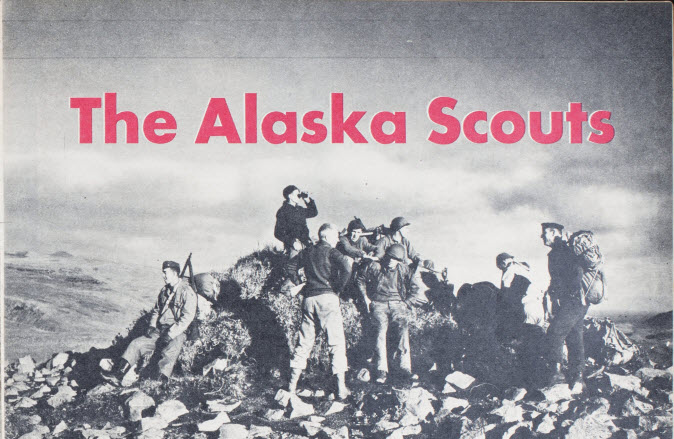

The Alaska Scouts

Ben Jeffery

A much overlooked and forgotten campaign of US operations in the Pacific took place miles from the tropic climes of Guinea, the bright lights of Singapore and the black sand beaches of Okinawa. These operations were carried out by a small task force in the North of the Pacific, on the island chain known as the Aleutians.

The Aleutians Chain is a set of 69 islands off the west coast of Alaska. The climate and topography of these islands are unforgiving, boasting steep mountains, rolling tundra and with plummeting temperatures. On the 3rd June 1942, a small Japanese force of roughly a thousand men occupied the islands of Attu and Kiska. Japanese military strategy reasoned that by occupying the islands they could prevent US movements across the North Pacific. Once occupied, the sparse populations of the islands were removed and imprisoned. For the US, the loss of the islands was a disaster. The Japanese could easily use them as a key stepping stone for the invasion of the West Coast.

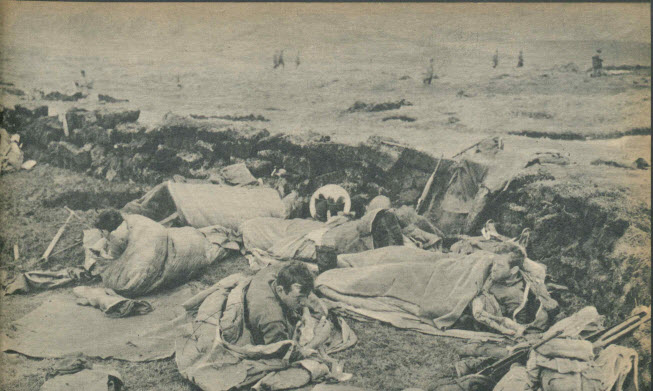

It is in the pages of Yank that we hear of the men given the task of braving the extreme landscape and taking back the islands. Known as ‘Scouts’, 24 men were recruited for the task. They came from a multitude of ethnic backgrounds; Inuit, Native Americans and Aleuts. These men were noted for their reluctance for taking part in Army routine and hardy nature. Many of them were miners, sourdough trappers and fishermen by trade and natives of the Alaskan and Aleutian regions. A testament to their efficiency in the island’s climate comes from the fact that they only resided in barracks after their winterized tents were removed while they were on operations. They performed vital reconnaissance missions, usually operating in small independent units. Fighting alongside them were the regular US and Canadian troops, but it would be the scouts at the forefront of the fighting and leading the way.

On the 11th May, the campaign to retake the islands was launched. The operation was met with severe logistical difficulties from the outset. Operations were further hindered by the Japanese defensive policy; they entrenched themselves away from the shore, inland and on high ground, much like they would later at Okinawa. By the 29th, the Japanese launched the largest recorded Banzai charge of the war. The ferocity of the attack at first caught the US forces off guard and the Japanese had considerable success, even reaching US rear echelon troops. They were, however, unable to consolidate their position and the Japanese force was all but wiped out. The islands were retaken and the threat to the West Coast neutralized.

Read more about the exploits of the 'Scouts' and the Aleutian Campaign in Yank